- Qualcomm Launches Snapdragon 4 Gen 2 Mobile Platform

- AMD Launches Ryzen PRO 7000 Series Mobile & Desktop Platform

- Intel Launches Sleek Single-Slot Arc Pro A60 Workstation Graphics Card

- NVIDIA Announces Latest Ada Lovelace Additions: GeForce RTX 4060 Ti & RTX 4060

- Maxon Redshift With AMD Radeon GPU Rendering Support Now Available

AMD Rejects BAPCo’s SYSmark 2012 – Should We?

In a rare move, AMD has publicly ousted a leading industry benchmark, BAPCo’s SYSmark 2012, released mere weeks ago. The company believes both that the benchmark is unfair in its weighting of scores, and also that it’s irrelevant for the average consumer. We delve deep into these claims, and offer up our own opinions.

Page 1 – Introduction; AMD’s Thoughts

Earlier this month, BAPCo announced the latest version of its SYSMark benchmarking suite, 2012. As with previous releases, we’ve been awaiting our copy to arrive so that we can take it for a spin and then decide whether or not it’s suitable for integrating into some of our content, such as our motherboard and processor reviews.

After learning that AMD has pulled out of its BAPCo membership, and has even gone as far as to make a blog post stating the reasons behind it, we’re not so sure at this point that SM2012 stands much of a chance of being used in our testing. We won’t know for sure until we receive our copy and can put it to a personal test, but AMD does raise some important issues.

The sole purpose of a benchmark is to provide useful metrics to consumers in order for them to make well-informed purchasing decisions, and where that’s concerned, AMD’s CMO Nigel Dessau has stated that “AMD does not believe SM2012 achieves this objective.“

While AMD’s press release on the matter doesn’t go into great detail, Nigel explores the reasons in an executive blog post. There, he stresses the need for “open” benchmarks that help provide the information consumers need to better understand how one product compares to another, and in the end can feel more confident in their purchase. As we at Techgage have shared a similar mindset since our site’s inception, we couldn’t agree more.

So what is it about SYSmark 2012 that has left AMD feeling sour? For as long as we’ve known about SYSmark, AMD has been right there, along with Intel, Dell, HP, Microsoft, Samsung, Seagate and others. Yet, this becomes the first large benchmark that I can recall AMD publicly ousting. We’ve never seen it happen with a Futuremark benchmark, or a SPEC. What’s the deal?

AMD’s largest complaint is that SM2012 doesn’t represent the market well enough, employing high-end workloads that the regular consumer doesn’t care about, and some that even favor its leading competitor. Prior to its launch, Nigel states that AMD had attempted to see BAPCo correct its wrongs, and release an offering much more ‘transparent and processor-neutral’, but the attempt proved unsuccessful. During the debacle, BAPCo allegedly threatened the termination of AMD’s membership (BAPCo denies this; full response added to the end of the article).

Before going further, let’s take a look at all of the applications included with SYSmark 2012.

- ABBYY FineReader Pro 10.0

- Adobe Acrobat Pro 9

- Adobe After Effects CS5

- Adobe Dreamweaver CS5

- Adobe Photoshop CS5 Extended

- Adobe Premiere Pro CS5

- Adobe Flash Player 10.1

- AutoDesk 3DS Max 2011

- AutoDesk AutoCAD 2011

- Corel Winzip Pro 14.5

- Google Sketchup Pro 8

- Microsoft Internet Explorer 8

- Microsoft Office 2010

- Mozilla Firefox Installer

- Mozilla Firefox 3.6.8

For a benchmark that has the goal of being a PC-wide test suite, the selection here isn’t too bad, though there is an obvious focus on workstation-esque applications. Of all the applications listed here, Autodesk’s 3ds Max is the only one we run as a stand-alone benchmark in our own testing (recent example).

Non-workstation applications include Adobe’s Acrobat, Dreamweaver, Flash player and Photoshop; Microsoft’s Internet Explorer 8 and Office 2010; Mozilla’s Firefox installer and the browser itself, and also Corel’s WinZip Pro. It’s interesting to note the introduction of ABBYY’s FineReader, an OCR (optical character recognition) application – a piece of software that couldn’t target the ordinary consumer much less.

It’s not the choice of applications alone that has AMD concerned, but rather the weight of some of them. In the same blog post, Nigel goes on, “a relatively large proportion of the SM2012 score is based on system performance rated during optical character recognition (OCR) and file compression activities − things an average user will rarely if ever do.“

I might disagree to some extent with the file compression note, since compression as a whole is a big part of computing, even if it doesn’t directly involve using an application such as WinZip. Application and game installers make use of compression and decompression, for example, but that’s of course something difficult to monitor, and an application such as WinZip is much easier to quantify.

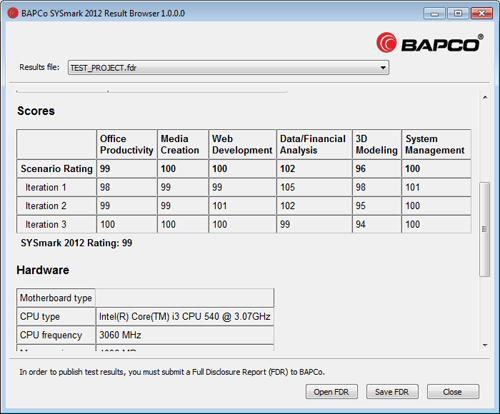

Further, AMD claims that while SM2012 includes 18 different applications and 390 separate measurements, a mere 7 applications and 10% of the total number of measurements determine the final score. We’ve contacted BAPCo for its input on this, but didn’t receive a response prior to publishing. Also, since there is no reviewer’s guide or whitepaper available on its website, we’ve been unable to investigate these claims.

Above all, a major beef AMD has with BAPCo is that SM2012 has little concern regarding heterogeneous computing – that is, making use of both the CPU and/or GPU. This might be the fairest point AMD makes here, as it’s something backed up by Intel (it has pushed its QuickSync rather hard, after all) and NVIDIA (whom arguably are responsible for most people first hearing about GPGPU).

This is an area where I once again feel inclined to agree. While most consumers are still not taking advantage of things like GPU video encoding, the GPU has been used in other areas where most people are affected, such as with video acceleration and UI rendering. At the same time, software that can make use of our GPU (Adobe Photoshop, as an example) continues to grow in numbers. Even our Web browsers can render pages with the help of our GPU.

Given the application list above, we can’t jump to conclusions and state that SM2012 does not make use of the GPU, because some of the applications listed can. We won’t be able to prove it to ourselves until we receive our copy and can monitor the GPU’s usage. For the sake of assuming that AMD wouldn’t have one of its executives lie in public, we’ll for the time-being just believe them.

After all said and done, does AMD make a compelling enough argument about SM2012? Should we ignore the prospect of integrating it into our testing? That remains to be seen, but I do admit that I’m inclined to withdraw from using it, unless there’s a specific scenario where using it still makes sense.

More of our own concerns on the following page.

Support our efforts! With ad revenue at an all-time low for written websites, we're relying more than ever on reader support to help us continue putting so much effort into this type of content. You can support us by becoming a Patron, or by using our Amazon shopping affiliate links listed through our articles. Thanks for your support!