- Qualcomm Launches Snapdragon 4 Gen 2 Mobile Platform

- AMD Launches Ryzen PRO 7000 Series Mobile & Desktop Platform

- Intel Launches Sleek Single-Slot Arc Pro A60 Workstation Graphics Card

- NVIDIA Announces Latest Ada Lovelace Additions: GeForce RTX 4060 Ti & RTX 4060

- Maxon Redshift With AMD Radeon GPU Rendering Support Now Available

A Look At Intel’s Core i9-9900K Performance In Linux

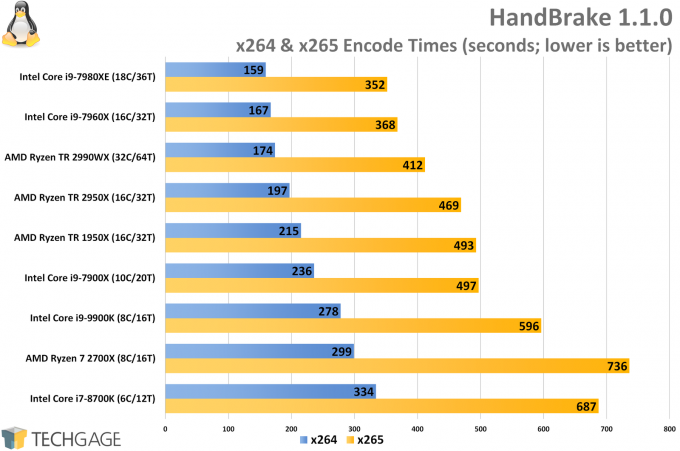

Eight-core processors are not a new thing, but eight-core processors that can reach a staggering 5GHz on a couple of threads are. How do those super-fast threads handle different scenarios in Linux? This article exists to figure that out, so join us as we see how Intel’s Core i9-9900K fares against eight other competitors.

Our look at Intel’s Core i9-9900K performance has taken far more time to deliver than we would’ve liked, but none of the reasons for the delay have anything to do with the product itself. Part of what held us back was the fact that so many product launches came at once, while another part had something to do with us overhauling and largely automating three test suites at once.

Nonetheless, our look at Intel’s 9900K is going to come in two spurts: the first is this one, tackling Linux performance, while the second will tackle the usual onslaught of Windows workstation tests, as well as some special gaming comparisons since gaming is a big marketing bullet-point for the chip.

This particular look isn’t going to be too in-depth, but as time goes on, our Linux tests will be expanded so that we can deliver a better overall look at the current performance landscape. We’d expect to post updated performance numbers with additional tests in the new year, so stay tuned for that.

As a quick primer, Intel’s Core i9-9900K is the company’s latest eight-core processor, and one that’s not locked into the enthusiast X299 platform. But eight cores for mainstream consumers isn’t all that’s interesting here. A major feature of the 9900K comes with its clock speeds, able to peak at 5GHz with one or two cores, or just a few 100MHz less when all eight cores are engaged.

Intel currently wins the IPC race, and that combined with the fact that it also delivers super high frequencies means that its 9900K is an extremely alluring chip either for work or games. And speaking of games, that’s one type of test we haven’t run in Linux for a while, but again, we’re continually looking at ways to enhance our content, so adding such tests in the future could happen. The same goes for workstation graphics tests, which we’ve recently begun prowling for.

Before diving into the results, here’s a look at our system’s test specs:

| Intel LGA1151 Test Platform | |

| Processors | Intel Core i9-9900K (3.6GHz, 8C/16T) |

| Motherboard | ASUS ROG STRIX Z390-E Gaming CPU tested with BIOS 0602 (October 19, 2018) |

| Memory | G.SKILL TridentZ (F4-3200C14-8GTZ) 8GB x 4 Operates at DDR4-3200 14-14-14 (1.35V) |

| Graphics | NVIDIA TITAN Xp (12GB; GeForce 396) |

| Storage | Host OS: WD Blue 3D NAND 1TB (SATA 6Gbps) |

| Power Supply | Corsair RM650X (1200W) |

| Chassis | NZXT S340 Elite Mid-tower |

| Cooling | Corsair Hydro H100i V2 AIO Liquid Cooler (240mm) |

| Et cetera | Ubuntu 18.04 (4.19.4 kernel) |

| Notes | The specs of the other five test platforms can be seen here. |

A total of six test platforms represent all of the tested CPUs, though that’s partially due to the fact that we’ve been using two of the same type of platform at once to speed up certain testing. Ideally, four machines would be enough to represent these four test platforms, and we reckon that will be the case once a test suite overhaul comes along.

For our Linux testing, a fully updated Ubuntu 18.04 LTS is used. The kernel itself was also updated to the latest 4.19.4 for the 9900K, while the other results were performed with 4.18.5 (stemming from our 2990 WX review). While it’s not applicable to CPU testing, the graphics-drivers PPA was added so that the NVIDIA graphics card could build a module with that modern kernel.

Before testing, a simple enforcing of the performance power profile is undertaken (as sudo):

echo performance | tee /sys/devices/system/cpu/cpu*/cpufreq/scaling_governor

Most of our Linux benchmarking is handled by Phoronix Test Suite, which makes it very easy to configure and run tests from a huge collection. Currently, HandBrake is run outside of PTS, and in time, Blender will likely be as well, since I’d like to expand on the type of testing done there (including GPU rendering in Linux). Other tests are also being considered, but like most things we want to do, our biggest limitation right now is time. If only there were some of that on sale this Cyber Monday.

But enough of that – let’s get to the results.

Compiling

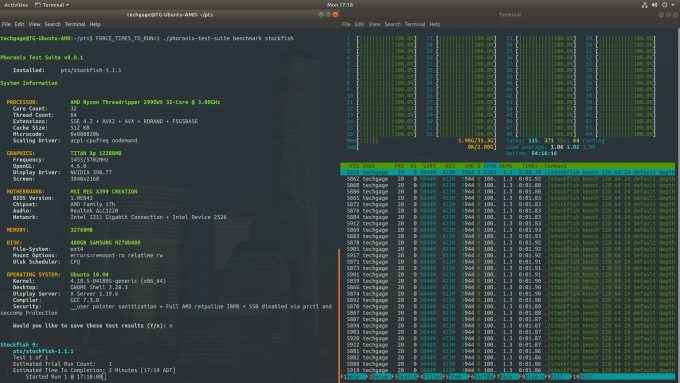

With a mere one second gap between them in the ImageMagick compile, it’s hard to feel too impressed with the 9900K here. Its advantage does increase with the kernel compile test though, so it’s not as though there are no gains to be had.

Another worthwhile comparison is pitting the 9900K against AMD’s Ryzen 7 2700X, as the respective chips are effectively the top mainstream offering from each company. Both are also eight-core models, and code compilation performs about the same on both, though as seen with ImageMagick, Intel still reigns supreme overall.

It’s interesting to note the performance differences between the 8-core 9900K and 10-core 7900X, as well. It seems that the higher clock speed of the 9900K helps it pull ahead of the 7900X with the ImageMagick compile, but the extra cores give the 7900X a big boost.

Blender

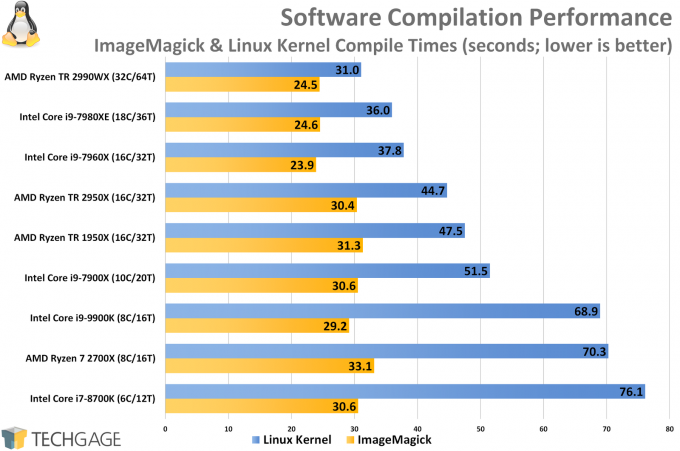

With Blender, the 9900K lands a fair distance ahead of the 8700K, giving us the kind of scaling we’d expect when moving from 6 to 10 cores – and not to mention the benefit of higher overall clock speeds. As we discovered a few weeks ago, AMD’s Radeon Vega architecture helps it deliver some excellent performance with Blender’s GPU rendering, but as we can see here, the company’s CPUs don’t really hold anything back, either.

Despite AMD’s strong Blender performance though, Intel’s game is still stronger, leading the 9900K to sit comfortably ahead of the 2700X. As with many renderers, Blender wants more cores, so if you opt for a beefier chip, your gains should scale pretty linearly. That scaling helps the monstrous 32-core Threadripper 2990WX dominate this chart.

HandBrake

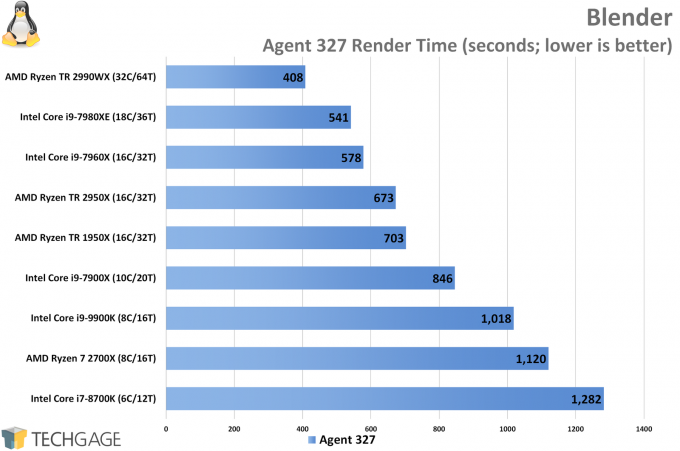

With HandBrake video encoding, the 9900K continues to leap ahead of the 8700K by a fair margin. The 9900K also once again beats out AMD’s Ryzen 7 2700X, with an especially strong lead with the H.265 HEVC encode. On the H.264 AVC side of things, the 2700X doesn’t fall too far behind. Intel’s HEVC performance is simply untouchable right now, which isn’t too surprising given Intel’s typically strong multimedia performance. Many encoders are built around Intel, and it really shows.

Still, even aside from performance optimizations, it’s not hard to imagine how beneficial 8 cores at 4.7GHz a piece would benefit this kind of work. The 9900K doesn’t just add cores, it helps each core get its work done quicker.

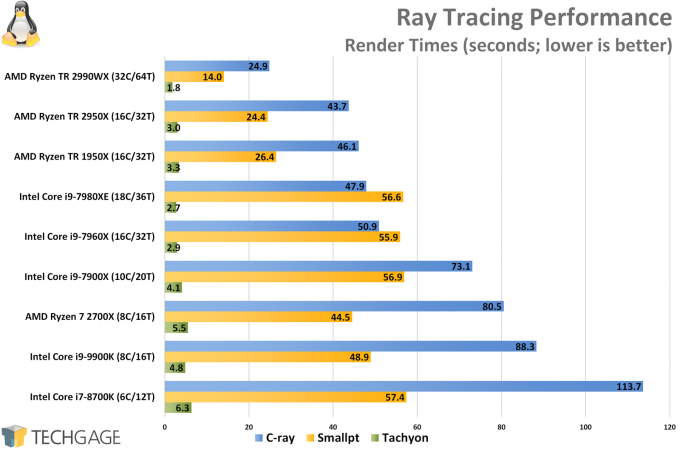

Ray Tracing

With ray tracing, different renderers can offer vastly different performance from architecture to architecture. There are a few cases with these results where that’s easily seen. We can take the 9900K, for example, which beats out AMD’s 2700X with the C-ray ray tracer, yet the roles reverse with Smallpt. As for Tachyon, the 2700X again pulls ahead of the 9900K.

As we saw with the Blender test, the more CPU muscle you have on tap, the greater the performance in any renderer should be. Thanks to that, the 2990WX once again tops the charts with a great lead. It’s worth noting that the 9900K performs quite a bit better than the last-gen 8700K as well, highlighting yet again that if rendering performance is important to you, you want as capable a chip as possible.

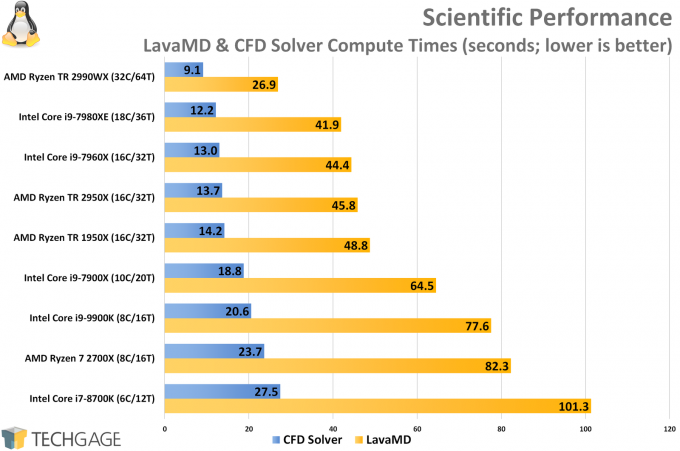

Scientific

These Rodinia tests represent some of the most demanding of our suite. Quite simply, you’d never run complex math on a lowbie chip, because the data is far too important to wait on. That’s why realistically, most of the chips in this list wouldn’t even qualify for this type of work, and it’s the perfect type of work to highlight the benefits of a massive core count as delivered with the Threadripper 2990WX.

With these results, the 9900K again places comfortably ahead of not only the 8700K, but also the 2700X. Meanwhile, the 10-core 7900X continues to iterate on the 9900K’s performance a fair bit – but the new 9900X costs at least $1,000, so the price of upgrading to that next performance level isn’t exactly for the faint of heart.

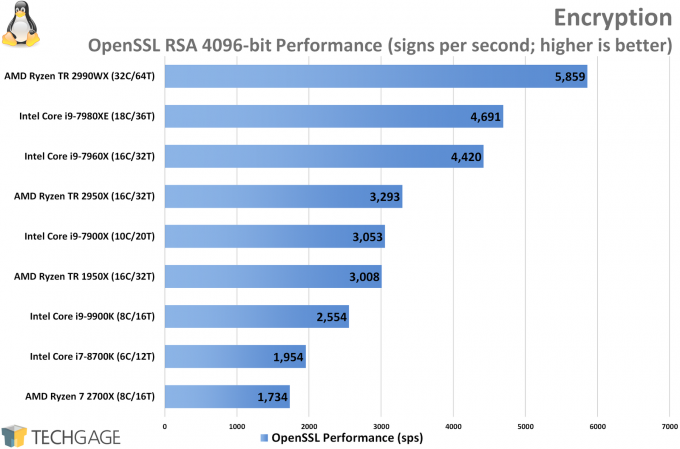

Encryption

With the OpenSSL encryption test, we can again see that the more muscle a CPU has, the better it’s going to rank in this chart. The 32-core Threadripper again tops the charts, with an 18-core Intel trailing behind. Meanwhile, we can see a big 30% improvement between the 8-core 9900K and 6-core 8700K.

AMD performs well enough in this test, but Intel definitely has an edge. The 16-core Threadripper 1950X performs effectively the same as the 10-core 7900X, although the newer 2950X edges a bit ahead. And then there’s the 16-core 7960X, which pulls far ahead of the newest 16-core Threadripper.

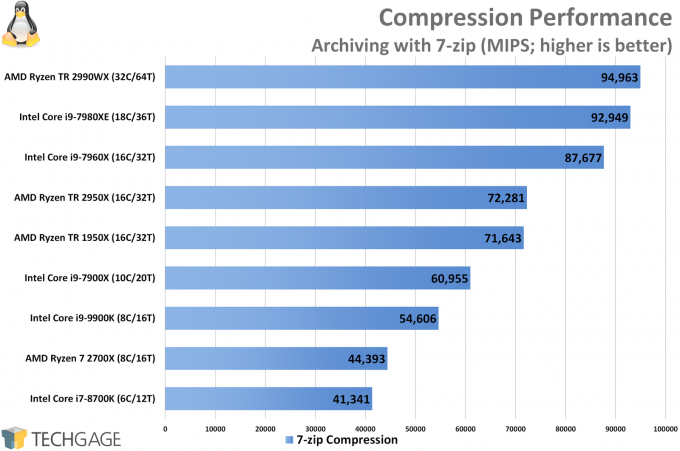

Compression

This compression test represents one of the strongest gains the 9900K has seen over the 8700K. It’s about a 32% gain here, which seems fair enough given there’s 33% more cores under the hood. While the Ryzen 7 2700X had no problem beating out last-gen’s 6-core 8700K, it’s no match for the 8-core 9900K.

AMD’s performance isn’t too impressive here, even though its top chip leads the pack. It effectively took 32 Zen cores to best 18 Skylake-X cores, but overall, both of the 16-core Threadrippers deliver great performance for the cost.

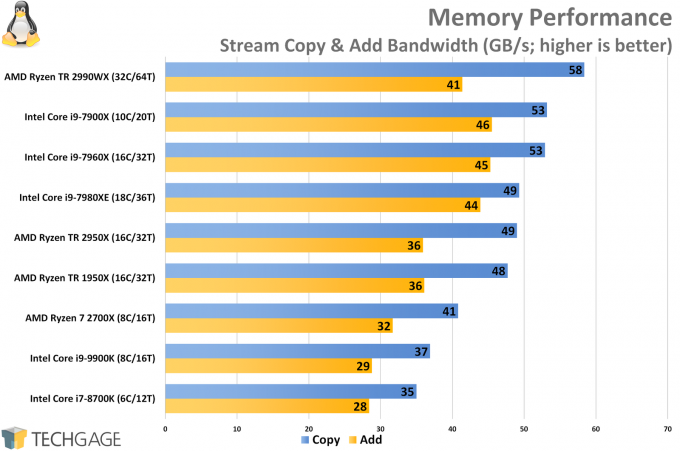

Memory

Its Zen architecture might not the most complementary towards memory latencies, but where bandwidth is concerned, AMD is a super-strong performer. The 2700X manages to beat out both the 9900K and 8700K at the exact same memory speeds of 3200MHz with 14-14-14 timings.

For the hungriest of applications, the quad-channel buses available on Intel’s X299 and AMD’s X399 deliver an obvious advantage here, with 50GB/s being a common sight.

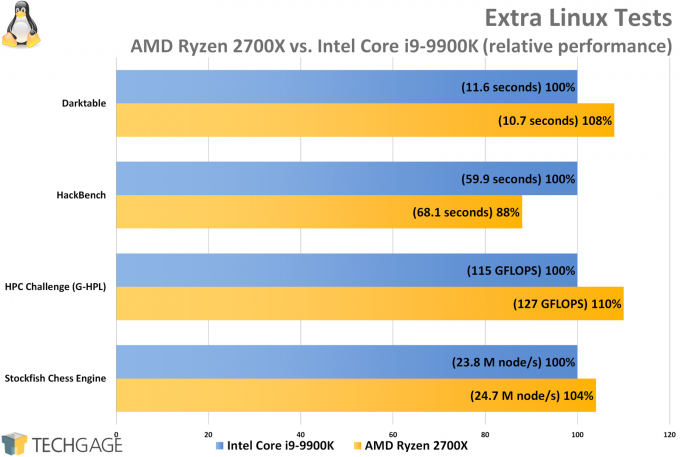

Extra Tests

The last time we published a dedicated Linux performance article, we tossed in some extra tests to accomplish just a bit more ground. Some of these tests will be included in the next suite overhaul, but each has to go through some analysis to gauge its true value. We’re admittedly not a fan of this Darktable test, because we’ve been unable to replicate the kind of hammering to the CPU that this synthetic test manages. Meanwhile, HackBench tests system call times, which is relevant to everyone, and really, who doesn’t love a good chess engine performance comparison?

That preamble aside, we didn’t expect this kind of performance to wrap up our testing. Interestingly, AMD’s 2700X beats out the 9900K in three of the four tests, falling behind only in HackBench, which is a test that thrives just as much on single-thread performance as it does multi-thread.

It’s important to note that while the 4.18.5 kernel was used for most of the 2700X testing on this page, the 4.19.4 kernel was used for both platforms with these special tests. Both used the same memory kit at the same verified speeds, the same SSD, and even the same graphics card (even though that’s completely irrelevant to this CPU testing). Apples-to-apples, AMD’s 2700X came out ahead overall here.

Final Thoughts

After poring over the data, the 9900K becomes an obvious upgrade to the 8700K, although if you’re already rocking last-gen’s six-core, there’s no strong reason why you should upgrade unless you know what you’re gaining – which is about 33% more processing power. In terms of cost, the next step-up to the 9900K would be AMD’s 12-core Threadripper 2920X, after which point the 16-core from AMD enters the scene at $1,000, which sits next to Intel’s 10-core 9900X.

While the 8-core 9900K already carries a big premium over last-gen’s 6-core, to take the next step will require a fair bit more money, unless you think the 12-core 2920X from AMD is worth your extra $150. We’re not even sure of that answer, but will be soon, as that and the 2970X are in process of being benchmarked.

Overall, the 9900K isn’t a difficult chip to read. It carries a price premium, but it’s also the fastest processor on the planet in terms of single-threaded performance, and 8-cores is a definite sweet spot – it’s not the meatiest in a landscape of 16- and 32-core processors, but it’s a lot better than 6 cores, especially given how many applications nowadays take proper advantage of as many threads as you can give them.

If we have any complaints about the 9900K, it’s mostly related to price, buuuut, this is a market-leading processor in terms of performance, so we can’t very well expect Intel to undersell it, despite how close the 2700X can get to its performance at times.

If you’re now craving Intel’s i9-9900K, it will set you back about $550. If you can find it in stock, that is.

Support our efforts! With ad revenue at an all-time low for written websites, we're relying more than ever on reader support to help us continue putting so much effort into this type of content. You can support us by becoming a Patron, or by using our Amazon shopping affiliate links listed through our articles. Thanks for your support!