- Qualcomm Launches Snapdragon 4 Gen 2 Mobile Platform

- AMD Launches Ryzen PRO 7000 Series Mobile & Desktop Platform

- Intel Launches Sleek Single-Slot Arc Pro A60 Workstation Graphics Card

- NVIDIA Announces Latest Ada Lovelace Additions: GeForce RTX 4060 Ti & RTX 4060

- Maxon Redshift With AMD Radeon GPU Rendering Support Now Available

Intel 4-Series Chipsets: G43, G45, P45

Intel’s next-generation chipset offerings in the mid-range and enterprise-level markets have arrived in the form of three mid-range offerings in Intel’s 4-Series of chipsets, including two with integrated graphics. In this article, we’ll lay out the differences, and help you understand your new options.

Page 1 – Introduction, P45 Express

While enthusiast chipsets like X38 and X48 set the performance bar high for Intel platforms, the real bread and butter of chipset makers like Intel, NVIDIA, and AMD, and often the more common choice of enthusiasts, is the mid-range product category. And it’s easy to see why – it’s usually possible to build a stable, powerful enthusiast system on the back of a mid-range chipset, and Intel’s P35 became a mainstay of gamers and price-conscious enthusiasts during its tenure for that reason.

Now, Intel is officially rolling out the successors to G33, G35, and P35, with the introduction of their 4-series counterparts, the G43, G45, and P45 chipsets. G43 and G45 feature an updated X4500 graphics core on-die, which provides DirectX 10 support for the first time in an Intel product, though NVIDIA and AMD have been there for some time now, while the P45 is essentially the G45, without the graphics processor.

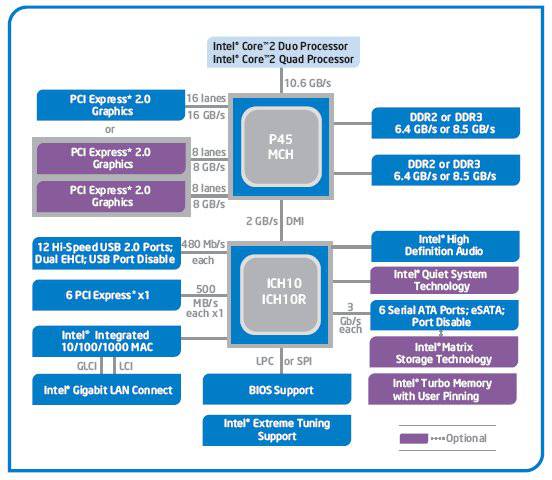

All three chipsets use the Intel ICH10 or ICH10R chipset, with the “R” variant offering support for a technology called “Turbo Memory”, which we’ll cover in detail later. There appears to be no difference between the ICH10 and the ICH9, except that the manufacturing process has shrunk to 65nm, reducing power dissipation. The northbridges themselves have also been transitioned to a 65nm process, for power savings and heat reduction.

We took a look at a P45 motherboard last week with our review of the ASUS P5Q Deluxe, and found that more than simply updating a few performance specs, as chipset makers are known for often doing, the Intel P45 had a nice surprise in store for us regarding its power consumption, shaving 33W off the measured power consumption of the test system when compared to the P35. Now, let’s dive into a summary of the other differences the three chipsets have to offer.

P45 Express

We’ll start with the top of the range, the Intel P45 Express. Intel’s chipset names have carried the “Express” moniker ever since support for PCI Express was added, but now that it’s the de-facto baseline standard for a motherboard to offer some form of PCI Express capability, the added meaning is a little empty. What isn’t empty, however, is the new chipset’s PCI Express 2.0 capability, which may be configured in a single 16-lane interface, or two 8-lane interfaces, for tandem graphics processing. AMD’s current mid-range performance chipset, the AMD 770, lacks Crossfire capabilities, though NVIDIA offers their nForce 750i MCP, which offers parallel-GPU processing in a more affordable package for the upper end of the mid-range category.

Let’s take a look at CPU support next. The P45 Express supports a front-side bus speed of 1333MHz, which means that FSB1600 CPUs like the QX9770 will be hampered. However, CPUs with a 1600MHz front-side bus make up a small segment of Intel’s current product line at the high-end, so you’ll likely want to pair these high-performance CPUs with an X48 motherboard anyhow. With the exception of the QX9770 and the Skulltrail QX9775 CPUs, however, P45 will work just fine with any current Intel CPU, including newer 45nm parts.

(As a brief erratum, the ASUS P5Q Deluxe report was incorrect in stating that the P45 supported FSB1600 – the P45 tops out at FSB1333. That article will be corrected.)

With regard to memory, the P45 Express natively supports dual-channel DDR2 800 memory on the DDR2 side (though more testing will reveal its true upper limit in practice, as the performance envelope is pushed), while supporting up to DDR3 1066 on the DDR3 side of things, though DDR3 operation cuts the chipset’s supported memory size in half from 16GB to 8GB. The stated maximum bandwidth under DDR2 is 12.8GB/s when in dual-channel interleave mode, and under DDR3, the stated bandwidth is 17 GB/s, numbers that the chipset pulls from dual 6.4GB/s and 8.5GB/s speeds on a per-channel basis. The P45 also supports “Flex Memory Technology”, which allows different-sized modules to be installed under dual-channel mode.

The P45 also supports a feature called Turbo Memory, which allows the chipset to use an additional NAND cache (similar to Windows Vista’s ReadyBoost feature — its use also requires Windows Vista) to host frequently-accessed data that can help speed up boot times and program access, as well as providing an intermediate cache between the hard drive and the operating system (again, exactly like ReadyBoost). Where Turbo Memory differs from ReadyBoost is that the NAND memory modules would in this case be installed directly onto the motherboard itself and housed inside the PC, instead of the half-baked solution of using an external NAND flash drive connected to a USB 2.0 port. The P45’s Turbo Memory implementation also offers a capability called “User Pinning”, in which the user may decide what data is stored in the Turbo Memory modules, if present. We suspect a complementary ‘auto mode’ may be the default option, however. Turbo Memory first showed up in Centrino Pro based notebook PCs.

On the storage side, Intel P45 supports a new feature called “Matrix Storage” technology, which allows external drives to be connected via eSATA ports and be included in a RAID array. The P45 also supports “Rapid Recover” technology, which allows users to create a “clone” of their system drive, and reload data from the “clone” if the main hard drive should fail or become corrupted. Lastly, the P45 supports disabling of individual external USB or SATA ports, to prevent malicious data from being introduced via an external hard drive or flash drive, and “Quiet System Technology”, which uses more advanced fan speed control algorithms.

The reason we covered the P45 first of the three was because much of its functionality is shared with the G45 and G43 integrated-graphics chipsets. Next, let’s look ahead to the P45’s integrated-graphics cousins, and see what variations are present there.

Support our efforts! With ad revenue at an all-time low for written websites, we're relying more than ever on reader support to help us continue putting so much effort into this type of content. You can support us by becoming a Patron, or by using our Amazon shopping affiliate links listed through our articles. Thanks for your support!