- Qualcomm Launches Snapdragon 4 Gen 2 Mobile Platform

- AMD Launches Ryzen PRO 7000 Series Mobile & Desktop Platform

- Intel Launches Sleek Single-Slot Arc Pro A60 Workstation Graphics Card

- NVIDIA Announces Latest Ada Lovelace Additions: GeForce RTX 4060 Ti & RTX 4060

- Maxon Redshift With AMD Radeon GPU Rendering Support Now Available

NVIDIA’s PhysX: Performance and Status Report – Part 2

It took a little longer than expected, but NVIDIA is soon to unveil new drivers that will open up PhysX support on all 8, 9 and GTX-series of GPUs. We’ve decided to follow-up on our previous article and see where PhysX stands today, and also pit seven GPUs against the new drivers.

Page 2 – 3DMark Vantage Performance

Around the same time I published the first part to this series, NVIDIA’s latest GPU driver at the time was getting a lot of attention, but for all the wrong reasons. I won’t delve into the entire backstory here, but I do recommend checking out that article for more information if interested.

The basic reason was due to the fact that their latest driver caused over-inflated 3DMark Vantage CPU scores, which was true. But, I’ll still stand by my reasoning that NVIDIA did nothing wrong, as they simply pushed the PhysX computation from the CPU to the GPU, which is the exact same thing that happens when you play a PhysX-enabled game with the same drivers.

If there was blame to be thrown at anyone, it would be Futuremark. After all, it’s their benchmarking tool that obviously focuses way too much on the CPU aspect. But on the other hand, the over-inflated scores are not really over-inflated at all. We all knew that GPUs excelled in certain areas where CPUs don’t, and PhysX-specific computation is apparently one of those examples.

The fact of the matter is, comparing the CPU result of an Intel Core 2 Extreme QX9650 to a GeForce 9800 GTX, for example, only goes to show just how much more efficient a GPU is in that certain situation. In the end, I don’t blame anyone, because there’s no blame to be had. 3DMark Vantage showcases how the GPU can excel at PhysX when compared to the CPU, and that in itself gives us some interesting metric to work with.

In the first article, I ran 3DMark Vantage in its entirety, but due to time constraints and the lack of a need, I’m going to focus on just the CPU results this time around. Included will be the overall CPU score (which includes results from the PhysX acceleration) and also the individual results from CPU test #1 and #2. Below are the descriptions of the CPU-specific tests:

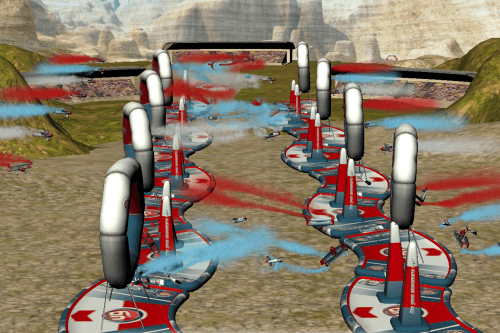

- Simulated Collision – Planes crash into each other in a realistic fashion.

- Simulated Fluid – Colored smoke trails each plane.

- Simulated Cloth & Soft Body

- Large hoops comprised of cloth material and can sway from the breeze of the plane.

- Pole gates simulate a foamy material, can also sway from the breeze of the plane.

If no PhysX accelerator is present, then the benchmark will fall back on the CPU. All results are displayed as ‘operations per second’, although the results screen itself calls it ‘steps/s’. Also, regardless of the mode selected, the CPU tests run in a fixed resolution, so scaling between GPUs is kept accurate.

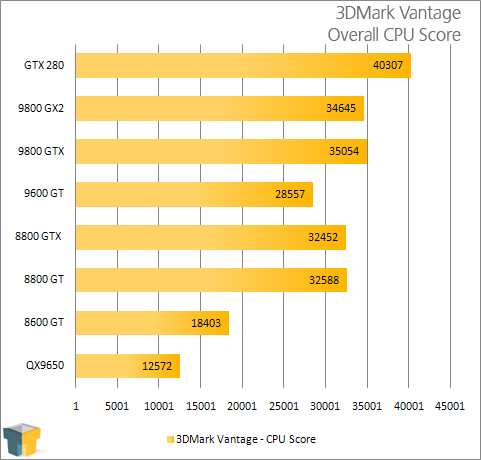

Let’s start off by taking a look at the overall CPU scores, both with PhysX acceleration disabled and also with it enabled. The differences are… well, undoubtedly obvious:

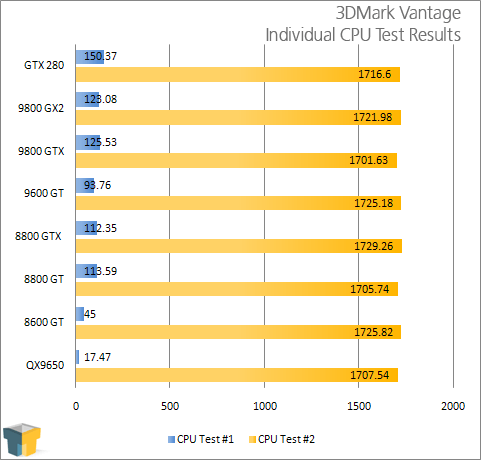

You can fine-tune the differences by seeing which test focuses on the CPU itself, and which targets PhysX:

It goes without saying that a faster GPU will allow greater PhysX capabilities, but that’s not much of a surprise. The rule of thumb when it comes to gaming with PhysX is the same rule of thumb for gaming in general: the bigger the card, the better the experience. The more performance a card can dish out, the better capable it will be to simultaneously handle both the graphics and PhysX at the same time. Small GPUs struggle.

But let’s face it, 3DMark Vantage is the least fun benchmark out there, so let’s move onto a real game, and a good one at that.

Support our efforts! With ad revenue at an all-time low for written websites, we're relying more than ever on reader support to help us continue putting so much effort into this type of content. You can support us by becoming a Patron, or by using our Amazon shopping affiliate links listed through our articles. Thanks for your support!