- Qualcomm Launches Snapdragon 4 Gen 2 Mobile Platform

- AMD Launches Ryzen PRO 7000 Series Mobile & Desktop Platform

- Intel Launches Sleek Single-Slot Arc Pro A60 Workstation Graphics Card

- NVIDIA Announces Latest Ada Lovelace Additions: GeForce RTX 4060 Ti & RTX 4060

- Maxon Redshift With AMD Radeon GPU Rendering Support Now Available

The Vicious Cycle of Gaming DRM

From music to movies to software and games, we can’t seem to use a computer today without encountering some form of DRM. That’s not even the worst of it, as the situation continues to decline over time. Taking a look at things from a gaming perspective, what can we do as gamers to help put DRM back on the right path?

Page 1 – Introduction

Copy protection has been at the forefront of tech discussion for a while, and it’s far from going away anytime soon. It seems that anytime we turn around as consumers, we’re finding a new threat to our rights as purchasers of a product. Historically, gauntlets have been thrown down with regularity between the RIAA, MPAA and their consumers – an ever-present reminder that we are little more than walking wallets to them, expected to buy what is offered simply because it’s for sale. One only needs to look to the looming ACTA arm-twist… err, negotiation to see that.

However, despite our arguments, one can honestly say that software as an industry, including games, has been quite generous in comparison. I’ve yet to see EA, Ubisoft or others walk around suing everything that moves because nobody bought the latest sequel. Aside from maybe Starforce, software copy protection has been a very gentlemanly cat-and-mouse. It certainly isn’t that the software makers have begged people to pirate their games, but they’ve at least had the decency to do little more than whine.

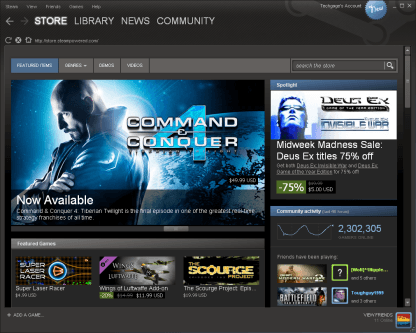

In reality, it seems that some copy protection was actually going forward and providing benefits, such as Valve’s Steam platform. The ability and convenience of Steam actually seemed to silence the debate for most products that used it, and even had people happy to trade piracy for a legal copy. DVD backups, instant patch delivery, digital downloads of new titles and DLC – it was like the best features of Xbox Live, without having to be constrained to the console. To this day, it remains (to my knowledge) the least thwarted copy protection system out there. Not because it’s largely uncrackable, as Valve often proposes – but because it provided features that make cracking it less valuable. That’s right, DRM (Digital Rights Management) provided a real service to consumers – it’s a lot better than it used to be.

Don’t believe me? Let’s take a trip down memory lane. Those of you who played games back in the days of DOS may remember a period of time where copy protection was handled by needing the manual with every startup. I remember back in the days of playing X-Wing how I used to need to go look up a word at the bottom of a page every time I’d sit down to play. This was all fine and good until my young puppy chewed the manual – and then I was screwed. That’s it, end of story, until I could find a copy of the manual somewhere or re-buy the game used. That, my fellow gamers, was copy protection circa 1985-1995. It existed, and the minute you lost a little book, you lost your ability to play the game.

By the time I went to college, copyright protection had moved on to simply requiring the CD in the drive to play. If you owned a legal copy of the game, this wasn’t much of a problem – however, it was touted as one of the greatest burdens in PC history. I’m not sure why “losing a CD” is more likely than losing a manual, particularly when you would need to retain the CD anyways in case you were to reformat your computer or need to reinstall the game. I’ll be honest, though – No-CD patches were becoming widely available, and their convenience was fantastic… especially on a college campus where all of us could play Quake 2 and Unreal with one CD between us. But that wasn’t piracy, because someone bought the game, right?

Fast forward a few more years and we enter the release of Half-Life 2 and the Steam platform. As mentioned, Steam offers so many wonderful benefits to gamers that it’s almost impossible to not want to buy games through it just to keep Valve promoting and maintaining it. But for all of its convenience, we started having the first real argument about who owned the content – Steam games could not be sold, could not be transferred. More importantly, they couldn’t easily be pirated, because your key was really a hash for the system that activated the game on your account, and not simply a crackable serial. Suddenly, gamers everywhere were incensed that their rights to sell the game after playing it were being taken away. And what happened if Valve no longer wanted to maintain Steam?

(Half-Life 2 was the first major title to utilize Steam’s internal DRM.)

As a side note, I honestly wonder exactly how many gamers really do sell old PC games. I’ve not discovered very many at all personally, though I could not hazard a guess at any real numbers. Bargain-bin prices being what they are, I would think that after a few months on the shelf you could acquire the same game new for less. I know that out of my group of friends and acquaintances who gamed over the years, console games traded hands or were sold outright quite often – but PC games were simply shared, not resold. As such, is the argument about the inability to sell, or the inability to pirate?

Anyhow, that is what the real progress of game-based DRM has been over the years. In that light, was it really so onerous and horrible? Granted, it’s all moot now – Ubisoft changed the rules and threw down its own gauntlet in January of this year. Buy the game, enjoy the benefits of Cloud DRM. No Internet? No game. Flaky Internet? Lost progress. It’s not quite “lost the manual, can’t get in the game,” but it also can’t be fixed by anything but cracking. One thing is for certain – if this is the future of copy protection, there will be a lot of very unhappy gamers out there.

Note carefully what I just said: a lot of very unhappy gamers, not less gamers. One only has to look on any torrent site to find cracks and workarounds to Ubi’s new big-brother protection. Not only is it cracked, but many of the crackers are now vindictive enough to interrupt Ubi’s servers with massive DDOS attacks, making the process intolerable to legal users who would have otherwise had no problems. Nobody in this debate seems to consider playing less games or different games as an option. Both sides are zealots, and every game is a new skirmish. So where one side finally stepped over the line, the other side has cut off the foot – but who is really winning? And more importantly, who is really losing?

Support our efforts! With ad revenue at an all-time low for written websites, we're relying more than ever on reader support to help us continue putting so much effort into this type of content. You can support us by becoming a Patron, or by using our Amazon shopping affiliate links listed through our articles. Thanks for your support!