- Qualcomm Launches Snapdragon 4 Gen 2 Mobile Platform

- AMD Launches Ryzen PRO 7000 Series Mobile & Desktop Platform

- Intel Launches Sleek Single-Slot Arc Pro A60 Workstation Graphics Card

- NVIDIA Announces Latest Ada Lovelace Additions: GeForce RTX 4060 Ti & RTX 4060

- Maxon Redshift With AMD Radeon GPU Rendering Support Now Available

AMD At GDC Talks Publisher Support, Epic’s Forward Rendering In VR & Radeon RX Vega

AMD is having a busy year, not only with hardware launches, including Ryzen and Vega, but also in the developer space, getting that hardware to work at optimum efficiency. One of the key focus areas right now, is VR development.

At its Capsaicin live stream event held at GDC, AMD talks about the challenges of VR and what it plans to do about it. Two key technologies were mentioned, Asynchronous Reprojection through SteamVR and Epic’s Forward Rendering pipeline in Unreal Engine.

Asynchronous Reprojection is something that Valve uses with its SteamVR content, as it’s a way to update the Head Mounted Display (HMD) when it dips below the 90 FPS frame rate, resulting in a smoother VR experience.

The underlining mechanics are that, when frame rates drop below 90 FPS, the graphics card will display the previous frame again, but adjust its position to track any updates to the head position. While not a true frame, it’s convincing enough to fool the brain into thinking its a new frame, preventing disorientation.

This is fundamentally similar to the Asynchronous Timewarp feature that’s been available on the Oculus Rift, however, Valve’s method used a graphics render path, rather than a compute unit. This meant porting the feature over is slightly tricky, and up until now, only NVIDIA GPUs have supported the feature. Being rolled out in the next Radeon and SteamVR update (some time in march), Vive users with AMD hardware will be able to use Asynchronous Reprojection.

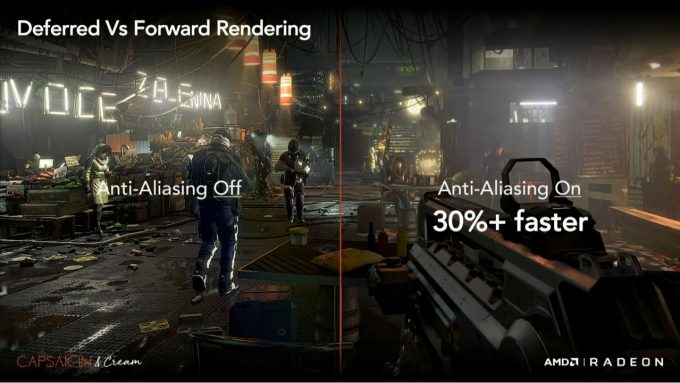

In addition to this, Epic Games, the creator of the Unreal Engine, have been experimenting with Forward Rendering, which is an older rendering technology used in new ways. When it comes to game rendering, most graphics engines use something called deferred rendering, where geometries are calculated first then shaded. This allows for very complex pipelines that can leverage all kinds of graphical effects. The problem is that while deferred rendering is good for image quality, it’s bad for latency, making high frame rates difficult for VR content.

A possible solution is to change the rendering pipeline to Forward Rendering. This system sacrifices some of the more advanced features and image quality, for low latency, high-speed rendering; critical when trying to maintain a minimum render speed of 90 FPS. (To be clear, this is Epic’s technology, not AMD’s)

Forward Rendering doesn’t throw image quality out the window though, but it does change what options can be used, while at the same time, allowing certain rendering techniques to be more viable. The example given was with MSAA. Because HMD resolutions are quite low at this time, anti-aliasing is important, since it removes the jaggies that are often visible at lower resolutions.

With deferred rendering, MSAA is impractical and bloated, so post-processing techniques are used for smoothing graphics, like FXAA. However, FXAA doesn’t work very well with VR content (everything goes blurry). Forward Rendering being lightweight, allows MSAA to be used more reliably, without causing too many issues with latency. Don’t be fooled though, MSAA is still demanding, but with a different rendering mode, its impact is lessened.

A number of demos were on show, with exclusive announcements for new VR games and content. Not only were these about pushing the boundaries of VR, but also showing off the performance improvements as a result of the new Unreal Engine update with the Forward Renderer. Consistently across the board, there were clear signs of a 30% improvement in rendering speed, while keeping the visual quality. Deus Ex Mankind Divided was one of the non-VR titles that showed such improvements, that was with MSAA enabled.

Back to the VR content, developer Survios of RAW DATA fame, was on stage to show off a new game called Sprint Vector. This is a new type of VR game that has motion and movement in it, without teleportation or static arenas. Sprint Vector uses what Survios calls Fluid Locomotion, which uses the player’s arm movements to simulate running, while using head tracking for direction control. By having the arms visible on the screen, it tricks the brain into a reference point and negates the motion sickness typical with visual movement from a fixed position.

Another key announcement is a bit odd in the grand scheme of things, as it’s one of those “why weren’t they doing this before…” moments. Moving forward, AMD will now be working with game publishers at a support level, rather than on a per title/developer basis.

In the past, AMD only worked with individual developers, typically on a single title, when it came to optimizing games. In partnership with Bethesda, the two plan on a long-term contract to leverage support in all upcoming titles for AMD hardware.

This support is built around leveraging the Vulkan API in modern titles, and this goes beyond just the GPU. The low-level API is as much about the CPU as it is the GPU, and with AMD’s Ryzen launch being the multi-cored beasts that they are, getting game engines to use those cores will be critical in AMD’s long-term strategy. By partnering up with a publisher, rather than individual developers, AMD can make a bigger impact and bring groups of developers around to new methods.

However, the real bang at the end of Capsaicin is AMD’s official brand declaration for the Vega GPU that so many have been waiting for. While it may come as a surprise to some, but RX 490 is not it, neither is it an RX 500 series. No, AMD has officially dubbed the card as, Radeon RX Vega.

If you want more details than that, you can check up on the tech brief AMD gave a month ago, but beyond that, it’s a waiting game for specifics such as core counts and pricing, but we should see something some time next month (March) about pricing and availability.