- Qualcomm Launches Snapdragon 4 Gen 2 Mobile Platform

- AMD Launches Ryzen PRO 7000 Series Mobile & Desktop Platform

- Intel Launches Sleek Single-Slot Arc Pro A60 Workstation Graphics Card

- NVIDIA Announces Latest Ada Lovelace Additions: GeForce RTX 4060 Ti & RTX 4060

- Maxon Redshift With AMD Radeon GPU Rendering Support Now Available

A Look At Phase One’s Capture One GPU Performance

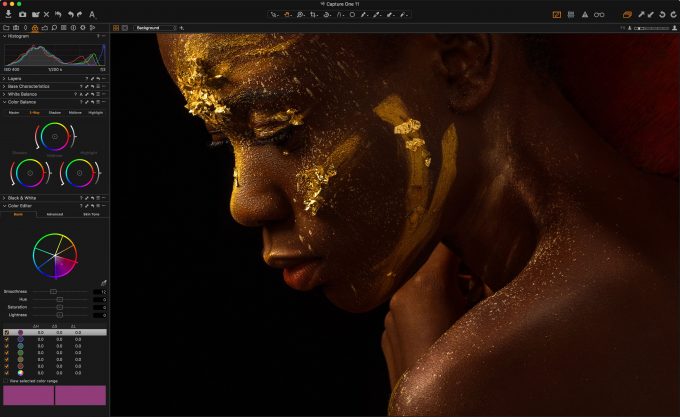

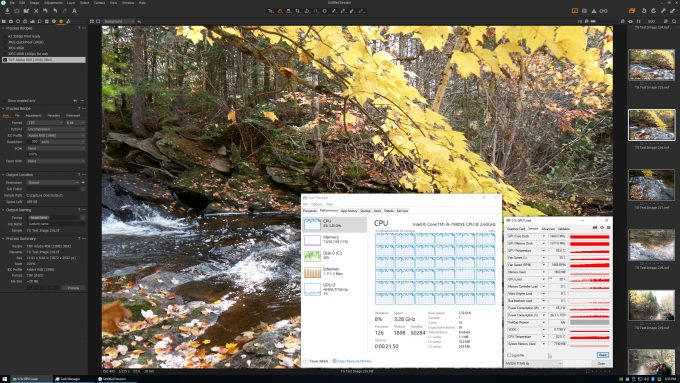

Capture One is a popular RAW photo editor that caters to the professional photographer looking for full control over their craft. In a land of competing products, CO stands out as being one of the few to take the GPU seriously, which is exactly why we decided to take the application for a performance test drive.

Whether you’re looking for cameras or their accessories, there’s no shortage of gear to ogle over in the world of photography. That even includes software. There are of course the mainstay image manipulation tools out there that everyone knows by name, but if you begin to dig for what else is out there, you’ll quickly find yourself going down a rabbit hole of photo enhancing goodness.

One of the first pieces of software a photographer needs, is an editor capable of handling every conceivable camera format they throw at it, and also enables the ability to edit throughout the entire process in a non-destructive way. Ideally, such a solution would also be bolstered with cutting-edge features, and engage the GPU to cut through those computationally intensive processes with ease.

Adobe’s Lightroom is likely the most popular RAW photo editor on the planet, a standing that was undoubtedly boosted by the popularity of its oldest sibling, Photoshop. While LR is a great tool in its own right, many have decided to make Phase One’s Capture One (CO) their home, as it complements their workflow better, or simply gives results that suit their tastes better.

While Lightroom takes light advantage of a system’s graphics card, CO takes things a bit further. With it, even the image export process is GPU-accelerated. That leads to an obvious question of: “Which GPU is fastest?” This article aims to answer that, at least in an initial manner (read: more testing could be done in the future, depending on feedback).

I am not a photographer, per se, but I decided to test out Capture One due to a request from a reader. Since I’ve been testing with Adobe’s Lightroom since it’s very first version, the thought of a more heavily GPU-accelerated editor seemed alluring. Unfortunately, these applications are rarely designed for benchmarking, so this is one of those rare times when I actually had to haul out a stopwatch (or rather, the clock app on my smartphone).

Using GPU Acceleration In Capture One

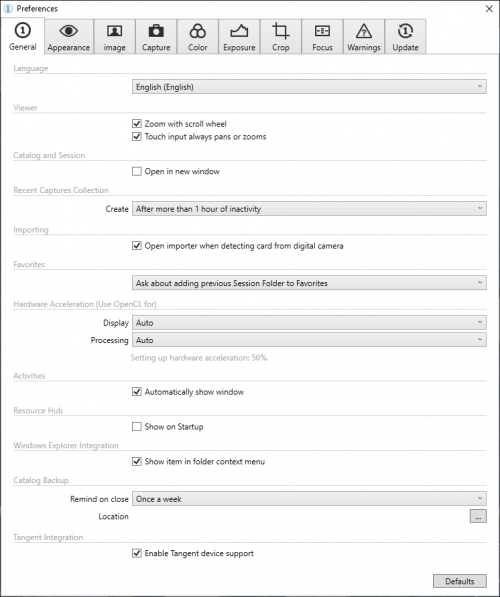

On its support website, Phase One says that Capture One can take advantage of any OpenCL-capable GPU, which of course includes AMD’s Radeon (and Radeon Pro) series, as well as NVIDIA’s GeForce (and Quadro) series. Whether or not the GPU is being properly utilized can be seen in the application’s general settings:

The setting up of GPU acceleration is a subtle process, one that’s done completely in the background if there’s a supported OpenCL processor detected. I am not exactly sure why, but this process takes minutes, not seconds, and it uses a small sliver of the CPU the entire time it does its thing. Once one vendor’s card is set up, a replacement card shouldn’t need to do this config process again (unless you’re changing vendors).

I ran into an issue a few times where GPU acceleration was broken, and neither reinstalling the application or the graphics driver would fix it. Whenever the fix did come about, I didn’t really have an explanation for it, but if you run into the same issue, you may wish to blast your graphics driver away with DDU (in Safe Mode), and try reinstalling it fresh.

Performance Oddities

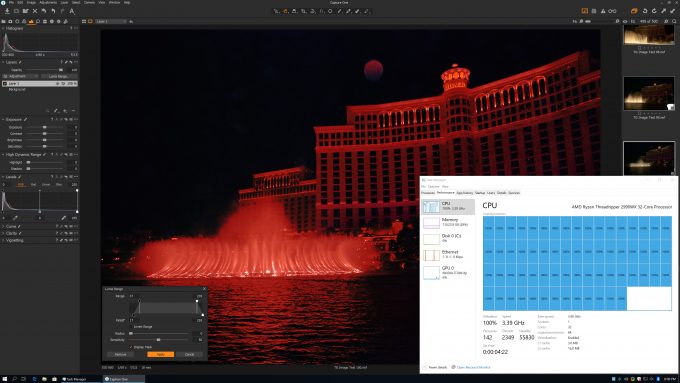

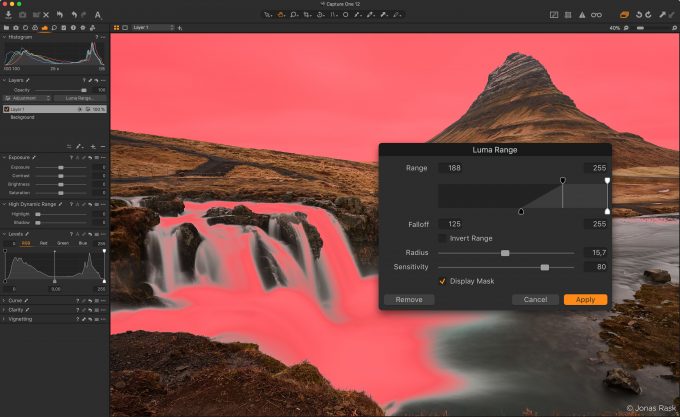

In experimenting with Capture One, I found its performance in certain areas to be hard to predict. When I installed the application on a machine using AMD’s Ryzen Threadripper 2990WX 32-core processor, I was initially stoked to see it using every single thread on offer (64, for the record):

This behavior was replicated on other machines, and ultimately, I feel like Capture One just doesn’t use the CPU that efficiently with all tasks; or, it at least uses too much of the CPU for the amount of work that’s getting done. In this particular case, the new Luma Range feature of Capture One 12 was being actively used, though I have seen similar behavior in other tasks. I couldn’t personally feel a difference between using this tool on the 32-core 2990WX or the 8-core 9900K.

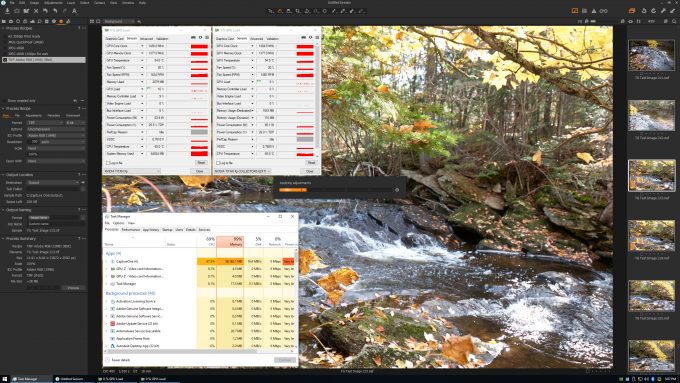

Another performance oddity comes to us in the form of multiple GPUs actually slowing down the overall image export process. On its support page linked earlier, Phase One says that Capture One can take advantage of up to four GPUs, as long as they are from the same vendor (in the end, they’re utilized as compute processors, so even Quadro+GeForce would be fine.)

In the shot below, you can see two NVIDIA TITAN Xps doing a little bit of work each, but ultimately, barely any work is actually getting done. When I tested an export process using a single TITAN Xp, it was about 5% quicker than it was when I introduced the second. These GPUs were not tested with a bridge, so SLI was effectively disabled, and each GPU was allowed to work as its own processor. I also tested dual Quadro and Radeon Pro mixed-model configurations, and saw the same results.

In this same shot, you can also see that Capture One can take great advantage of the memory you have – or, it can at least use all of it if you let it. With this test, I had copy and pasted adjustments from one file to the other 499, which left the total memory used at about 32GB. After running the same process again, that 32GB increased to 40GB, and so on and so forth.

After multiple applications of my adjustments, the memory ultimately became exhausted. I had Capture One crash on me a couple of times when using it on a PC with 32GB of memory (without nonsense repeated testing), so I feel like the application could be smarter about releasing memory when it’s no longer needed, although Photoshop can exhibit similar behavior. Again, this could be personal experiences that really only came about for someone who’s trying to eke the highest GPU usage out of it, rather than using it as intended.

Capture One Performance

There are a number of ways an application like Capture One could be used to generate some benchmark results, but in my testing, I found simply exporting a batch of images yielded the highest amount of GPU use. Applying a handful of adjustment layers across a large collection will also use the GPU to a decent degree, but exporting can use about 10% more of the GPU on average. This is important to note, because while applying adjustments can cause a GPU to spike to ~60% and give the impression of increased effectiveness, the gaps between those spikes is much wider than they are with an image export, resulting in a lower average overall.

To figure out the best test, I used Capture One in different ways, and monitored the GPU usage the entire time. You might be surprised to learn that often, the GPU really isn’t called upon in a big way too often – or at all, depending on your definition of “great”. In testing, I couldn’t surpass 38% average GPU use, and often, it hovered more around 25~30%.

For an image processor, this really isn’t too bad at all. In most of my video encode tests, I usually see the GPU peak at around 60% average. Rendering is where you’ll see that % burst to 100. Otherwise, many processes happen so quickly, you won’t really be able to appreciate what the GPU even did for you.

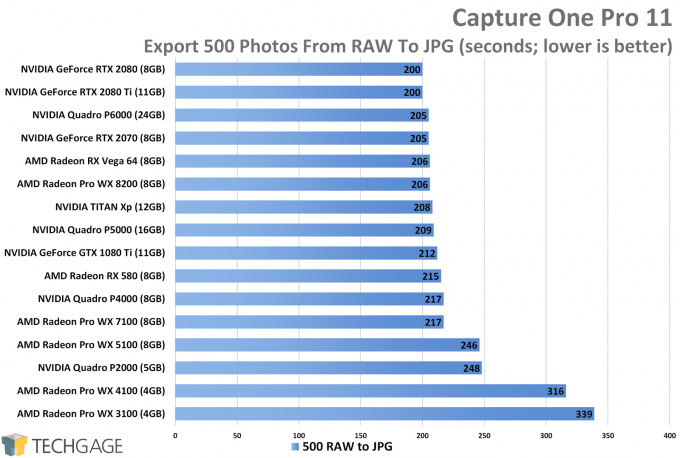

For the test results below, I exported 250 .NEF and 250 .CR2 RAW photos of about 10 megapixel in size to JPGs of the same resolution. After I concluded testing, I discovered that I should have exported to TIFF to represent a more realistic scenario, but after further testing with both CO 11 and 12, I can say the difference overall was mild to the point where it basically felt the same. That’s not to say there won’t be differences in some scenarios, but I couldn’t see noticeably different results across multiple GPUs.

All of that culminates in the results below, which quite frankly are not too interesting (so it’s a good thing I had other randomness to fill the page above).

The results seen here reflect the kind of scaling we often see with video encoding, with a great example being Adobe’s Premiere Pro CC 2019 (stolen from our Radeon Pro WX 8200 review). There are good and bad aspects to this. On one hand, it’s nice to see that you don’t need to go with a high-end graphics card to get good performance out of Capture One. On the other hand, it’s unfortunate that those with higher-end cards already won’t see much of an advantage in this particular application.

As alluded to earlier, I am certainly not a master of CO, so it could be that others could push it harder, but I spent quite a bit of time trying to push the GPU as much as possible, and I only got so far.

Final Thoughts

Techgage receives numerous requests to benchmark different creative and design applications, and I can tell you that we do keep track of them (and plan to tend to some when time allows). Capture One caught our attention because it’s a RAW editor that actually uses the GPU in a considerable way. I’ve been testing Adobe’s Lightroom since the first version, and yearned for richer GPU support for many years. While some support does exist, we’re sure to see it grow as Adobe seems hellbent (in a good way) in accelerating all the things lately.

As much as I’ve used Lightroom, though, Capture One really grabbed me, and tried to convince me that hauling out my Nikon D-SLR should be done more often than just for review photography. It’s a professional application, but it doesn’t take long to get to a point with CO where you feel like you have a good grasp on things. Phase One itself has a great tutorials section for users just starting out, and others wanting to brush up on techniques.

At the current time, Capture One Pro sells for $299 for a standalone license, or $180 for an annual license. Phase One offers a number of bundles that include style sets that cover a wide range of effects, such as film aesthetics and black and white variations.

If you’re actually learning about Capture One before you settle on a new camera, Phase One itself offers a couple of different models worth checking out. That’s another differentiator between Phase One and Adobe – the former makes both hardware and software. Worried about megapixels? Don’t be. The XF IQ4 150MP has as many megapixels as its name implies, delivering images at 14204×10652 resolution.

The XF IQ4 150MP retails for about $50,000, so with the software included, that’s about $50,300 to get kick-started with a high-end photography solution. Of course light tents, backdrops, and mounts and such are going to add hundreds of dollars to the final tally, so you’re going to have to think hard about whether you should bite the bullet!

Support our efforts! With ad revenue at an all-time low for written websites, we're relying more than ever on reader support to help us continue putting so much effort into this type of content. You can support us by becoming a Patron, or by using our Amazon shopping affiliate links listed through our articles. Thanks for your support!